FROM THE BLOG EDITION: http://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/key-weather-phenomena-to-follow-in-2016-52260

Right from unprecedented episodes of "unseasonal" rain and hailstorms in early summer to severe floods in the late monsoon, 2015's weather kept everyone on their toes. Most of these events didn't occur out of the blue but the way they impacted us (for instance the March floods of Kashmir) showed a lack of preparedness. The impact of 2015's weather phenomena like the poor monsoon is so severe that sustaining lives in parched areas like Marathwada of Maharashtra, Bundelkhand of Uttar Pradesh and numerous villages of Madhya Pradesh till the next monsoon is going to be very difficult. Agriculture is the worst-hit in these regions and water levels are critically low (especially in parts of Maharashtra). Eventhough summer is months away, a large number of tankers are already being used to provide water, which shows the severity of the drought.

As 2015 was the second consecutive year of below normal monsoon rainfall, all eyes will be on the monsoon of 2016. But other meteorological phenomena will occur too, which should not be underestimated as they would have the potential to take a heavy toll. The interesting thing is that these annual weather phenomena are set to occur in India in 2016 but no one knows how strong or weak they would be. This is because of the inability of weather models to give precise information of the weather over a time scale of many months. The intensity of weather events generally doesn't repeat on yearly scales. For example it isn't necessary for 2016 to be a below-normal monsoon rain year just because 2014 and 2015 were. But learning from past weather events definitely helps in preparing better for the next impacts.

El Niño nearing peak intensity

IMAGE 1: Weekly Sea Surface Temperature anomalies showing domination of El Niño (black dotted circle). Red colour indicates significant above normal sea surface temperatures

Courtesy: NOAA/ESRL/PSD

Before we look at the aforementioned meteorological phenomena, it is important to take a look at the present status of El Niño in the Pacific Ocean. It is pretty strong and is already producing significant global impacts such as recent flooding in the United Kingdom and globally high temperatures. But data of Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomalies in the equatorial Central Pacific Ocean suggests El Niño nearing its peak intensity or perhaps it has already peaked and henceforth, will start decaying. It is likely that this El Niño will be placed in the top three strong El Niño events (1997-98, 1982-83) ever recorded since 1950. El Niño conditions will definitely continue for some period in 2016.

Behaviour of Western Disturbances till monsoon of 2016

IMAGE 2: Rainfall in India between October 1 and December 23, 2015. India has received 20 per cent below normal rainfall in this period.

Courtesy: India Meteorological Department

Frequency and intensity of western disturbances impacting North India have been lower in 2015 (i.e October onwards). Stronger western disturbances often produce effect (i.e rain) on the plains of North India which is beneficial for proper growth of winter crops. But, as India is yet to witness such a powerful system, the post-monsoon rainfall situation in the plains of North India remains grim. Between October 1 and December 23, Delhi got just 5 per cent of its normal rainfall. More observations suggest that between October 1 and December 29 2015, Palam has got just 2mm rain (27mm less than normal), Safdarjung just 1mm (39mm less than normal), Chandigarh 19mm rain (40mm less than normal). Interestingly, Jammu and Kashmir has got excess rainfall as the western disturbances have been highly localised until now.

The first thing to look at in 2016 would be the frequency and intensity of western disturbances when they strike North India. Their strength in January and February will be a deciding factor for states like Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. Jammu and Kashmir's water reservoirs largely depend on snow streams and net snowfall/rainfall determines the state of agriculture, flora-fauna, tourism etc. Any prolonged dry spell or irregular precipitation patterns in these months will have the potential to affect these states. In the plains of North India (particularly Delhi-NCR), improper rainfall patterns or scanty rainfall in these two winter months will not be of any help in cleaning the air i.e reducing the air pollution.

Mid-February onwards, temperatures in the hilly areas start increasing and rise above the freezing point in many regions. March witnesses warmer days and hence, snowfall gets converted to rainfall in these areas. Due to this rain, flooding potentials increase considerably in rivers like the Jhelum and subsequently in cities like Srinagar which was observed in March 2015. An increased and intense western disturbance activity in March 2015 flooded Srinagar and parts of the Kashmir valley, causing heavy damage. Thus, the behaviour of western disturbances in these months needs to be closely followed.

Summer season thunderstorms

Here, summer refers to the months of March, April and May. In India, the transition from winter to summer takes places in March and that is why, this month is a bit unstable in terms of weather. The weather in these months is very vital for agriculture as Rabi crops mature and are harvested around this period. So, any widespread rainfall or hailstorm event damages these crops as well as horticulture. That is why, the best way to safeguard these crops would be effective implementation of the crop insurance scheme and making sure all varieties of crops (including horticulture) come under it. Farmers must keep harvested crops in dry places without waiting for any advisories.

Since the past few years, India is witnessing multiple days of severe thunderstorms (including hailstorms) in these months. The hailstorm event of 2014 and "unseasonal" rain event of 2015 significantly impacted India's agriculture which broke the backbone of the farmers. Increased interference of western disturbance was the main reason behind these severe weather events. Thus, any such event in 2016 will prove to be catastrophic, especially in those areas where agriculture distress is at its peak. But if such thunderstorms occur in drought-hit villages such as those of Maharashtra or Madhya Pradesh, the associated rain would bring temporary relief. Under a strong thunderstorm season, effects of ongoing drought could also reduce.

Not to forget, these thunderstorms, along with associated lightning strikes, have been a major killer in India. They have killed more than 2,500 people in India in 2014. Hence, the behaviour of western disturbances and thunderstorms in March-May 2016 also needs to be closely followed.

Temperatures and duration of summer season

IMAGE 3: Temperature anomalies during March-May 2014 and 2015. Yellow to red shades indicate warmer than normal temperatures whereas bluish shades indicate cooler than normal temperatures.

Courtesy: NASA GISS

We know that 2014 is the warmest year (so far) recorded since 1880 but 2015 is likely going to take this position as per World Meteorological Organisation. "The global average surface temperature in 2015 is likely to be the warmest on record and to reach the symbolic and significant milestone of 1° Celsius above the pre-industrial era. This is due to a combination of a strong El Niño and human-induced global warming" according to a release of World Meteorological Organization

Despite some heatwaves and overall global heating, India didn't witness any significant heating in the March-May period of 2014 and 2015 as can be seen from above image. In fact, some cooling signs (white to light blue shade suggesting negative temperature anomalies) are visible in these periods, which are likely due to a plethora of clouds and rain. In any summer season, the skies need to remain clear for temperatures to increase but frequent clouding and rain episodes cause cooling and hence reduction of summer season. We may dislike the summer but proper heating of the Indian Subcontinent is vital for various ecosystems. It is believed that because of this summer heating, a low pressure establishes over Pakistan-North-West India which anchors the south-west monsoon winds. But, a milder summer season can be a boon for parched areas as lesser the temperatures, lesser will be the evaporation of water from water resources. Sustaining lives under such a scenario will be comparatively easy.

Hence, in a background of global warming and devolving El Niño, temperature anomalies during 2016's summer will play a major role in India's weather.

South-West and North-East Monsoon Season

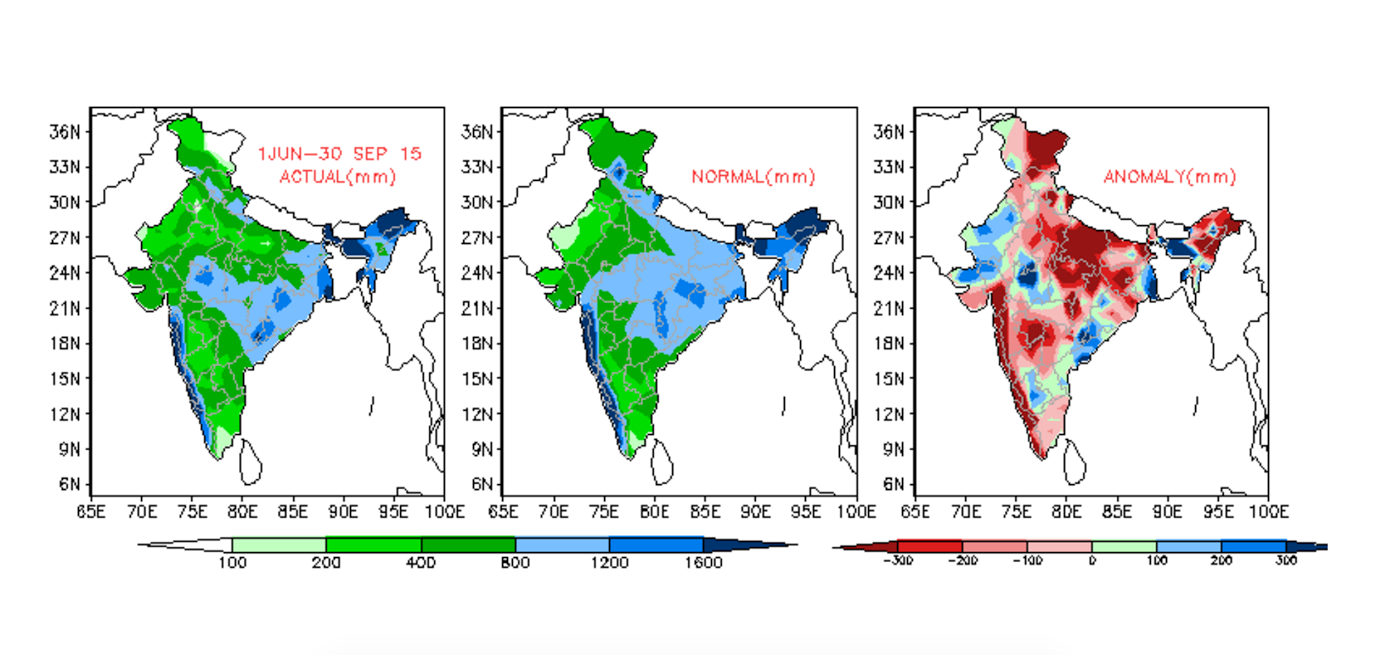

IMAGE 4: Normal VS actual performance of South-West Monsoon of 2015. Red shading in right side image shows areas which have received very low monsoon rainfall.

Courtesy: India Meteorological Department

Undoubtedly, the South-West Monsoon of 2016 would be the most important and highly-followed weather event of 2016. This can be understood from the fact that it is many months away but guesswork on how it would be, has already started on the internet. Already, mixed reactions are coming from various people/agencies which usually start coming after April when the India Meteorological Department issues its first stage monsoon forecast.

The key debate at present is on "El Niño or La Niña" during the next monsoon. Present estimates (of course all estimates are subjected to change) from Climate Prediction Centre of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) suggest that El Niño conditions will persist till late spring or early summer of 2016 (i.e around June-July) following which, a transition will take place to neutral conditions (known as ENSO Neutral). El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) exists in two modes: El Niño (bad for monsoon) and La Niña (good for monsoon). But, when both are absent (i.e Pacific Ocean has normal sea surface temperatures) then it is called ENSO neutral.

The latest update of the second version of Climate Forecast System model (which is popularly used in ENSO forecasting) expects El Niño to continue through June-August 2016. The Bureau of Meteorology of Australia doesn't expect the end of El Niño to happen at least till autumn of 2016. Moreover, the present forecast of Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) doesn't indicate any positive IOD event during next year's monsoon. A positive IOD tends to be favourable for monsoon. Thus, at present, there is a sort of disagreement between the models and agencies which will likely continue in the coming period given the mischievous nature of ENSO and IOD.

So, if El Niño persists through the early monsoon of 2016, the million dollar question would be whether it will remain that strong to influence the monsoon. It is definitely going to be challenging for monsoon prediction models to give a precise forecast of India's monsoon in 2016.

Amidst all this, we certainly know one thing, which is monsoon's intra-seasonal variability which affects the distribution of rain over space and time. The above image clearly shows monsoon rainfall variation. In 2015's monsoon, eastern Madhya Pradesh got very less rain as compared to the western part. An increase in extreme wet and dry spells of monsoon is very well documented in parts of India like Central India. So, authorities need to monitor such spells (particularly those occurring in sowing months like June) more carefully to avoid any 2015-like situation (in which sowing took place speedily but then, the rain disappeared).

India badly needs a proper and well-distributed monsoon rainfall in 2016 but any irregularities will be capable of impacting the Kharif season and worsening of the drought scenario. Likewise, the North-East monsoon season will also be a thing to watch for South India.

Tropical Cyclones

2015's cyclone season for India was relatively quiet as compared to previous years. Excluding Cyclonic Storm Komen (July 26-August 2), no tropical cyclone hit the mainland of India. The most interesting thing was that this year, the Arabian Sea was more productive than the Bay of Bengal (the situation is usually reverse) and Komen was one of the few cyclones to have formed in the peak monsoon season. As a result of low cyclone activity in India, damage due to them has also been less. But, under a warming Indian Ocean scenario, it will be interesting to see how many cyclones form and where they head.